My father suffered from an addiction that led to his incarceration. Now? It’s time to break the silence about what that meant for both of us.

For the first time in my life, I’m ready to talk about a secret I’ve held on to for the past twenty years. I’m one of the 2.7 million children in our country with a formerly incarcerated parent.

I share my story because often, children of addicts and children of inmates are silent victims. I share my story because I understand the shame, guilt, and anger you feel when someone you love suffers from addiction. I share my story because having an addicted loved one is often life-changing, and we deserve some self-pity and understanding sometimes. Mostly, I share my story to let you know that you are not alone and that we don’t have to continue our struggles in silence.

Addiction is a powerful force. It can change your life in the blink of an eye.

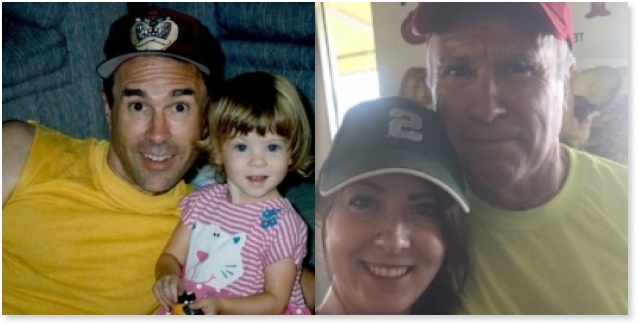

To be honest, that’s how it felt for me. I know now that his addiction and illegal acts were occurring before I was born, but at the time, it all seemed to happen so fast. One day I was a child, just shy of three, living with my two parents, brother, sister, and two dogs in an upper-class neighborhood in Tempe, Arizona. Then comes the divide in my memory. There is a distinct “before” and “after” in my childhood memories. Before just seems like it was some fairytale wish in my young mind.

The moment “after” began is still clear as day in my memories; I remember having to stay inside, behind closed drapes, because reporters weren’t leaving us alone as they tried to cover this “prestigious judge’s arrest.” I remember entering a very dark, gray building that was covered in rows and rows of razor wire. I remember being surrounded by cops and just knowing that “we were going to see daddy before we moved,” but not understanding why daddy was here. I remember my dad in a green jumpsuit and taking a family photo against a cheerful backdrop, like we weren’t inside a maximum security prison. I remember it being time to go and screaming “I want my daddy,” over and over, until I was hysterical. No one listened; he was still taken away. I remember not understanding. Other than that, all I knew from this point on is that “daddy is in trouble and daddy is in prison for a little while.” This was the last time I saw my dad for five years.

My dad is an extremely intelligent and educated man.

He was at one time the top presiding judge in Tempe, Arizona. He was only twenty-six when he was sworn in, making him one of the youngest in the country. He was a dedicated father, and we seemed to have everything we could want. He had also been gambling since he was thirteen.

In April, 1995, my dad pleaded guilty to single counts of fraudulent schemes and artifices, bribery, theft of public money, and conspiracy to obstruct a criminal investigation. This charge was a result of a scheme that funneled more than $478,000 to my dad to pay off heavy gambling debts. After over twenty years of an addiction, he was forced to stop, because he simply ran out of money. He said that his addiction did not merely contribute to his incarceration, but was the sole and complete rationale, reason, and cause for it.

By the time he reached the final stages of addiction, gambling was the only relevant factor in his life’s pursuit and direction.

He was no longer in charge, and having turned his life, emotional structure, and sense of personal responsibility and moral direction around, he had no conception of consequence or feeling of regret for his actions. The possible consequences were never considered. He said that his addiction destroyed every valuable part and component of his life and that the single most lingering pain is the trust, love, and time he lost from those he loves the most. The impact of this revisits him on a daily basis, seventeen years after his release from prison. The realization of how his addiction and actions have altered his life are hard to come to terms with. During his time in prison, he felt like he failed the ones who counted on him for everything. The process of coping and healing is one that takes a lifetime to repair and work towards.

While in prison, my dad struggled to find treatment.

He said that getting the right services is not merely helpful, but an essential life support system during a time when someone’s life is ruled by addiction. This help is not something he found during his incarceration. He feels as if addiction is purely a medical problem as surely as cancer, diabetes, or AIDS, and as such it requires a medical solution. Until such time as a medical solution is found, addiction’s accompanying social, legal, and moral problems can’t be effectively addressed; let alone solved.

Thus, life lived in the “after” became normal. In the beginning, I remember a lot of tears. I can clearly recall the stress and pain on my mom’s face because she wasn’t sure what to do. My mom was diagnosed with a genetic heart defect before I was born. It was slowly but surely progressing into congestive heart failure. The arrest of my dad seemed to be progressing her symptoms. She now had to worry about raising three kids under the age of ten alone on top of her disability. In the early months after our cross-country move to Michigan, I spent a lot of time curled up on her lap with a box of tissues. I remember wiping her tears and telling her it would be okay. My mom’s needs became my biggest concern. Everything that was going on inside of me sort of internalized. Our privileged lifestyle was yanked away and replaced with poverty. This was when my vow of silence started; I wouldn’t speak of my situation to anyone, not even friends.

Growing up in a rural town in northern Michigan with a population under 10,000 did not particularly encourage me to break my silence. There wasn’t much diversity, and I felt like the only different one. I was constantly aware of the differences setting me apart from this middle-class world. If anything, my vow of silence intensified. I hid parts of my reality, but it was sometimes difficult. In a small town, people know too many intimate details of my life. Even from a young age I knew there was a negative stigma associated with the details about my life that they knew. Everyone knew I lived with a single mom who had a disability. I did all I could to prevent adding “child whose dad has a gambling addiction and is in prison” to this label. We learn from an early age that “bad guys” get caught or that “bad guys” go to jail. But I never saw my dad as a bad person. He was my dad, after all.

I closed myself off from others out of shame, fear, and embarrassment over my situation. I felt terrified of how people would view me. I was petrified of being judged. I was angry at my dad and the life I was given. I never spoke up because I didn’t think anyone would understand. How could they possibly understand my sadness, stress, and pain? I couldn’t risk them shaming me or shaming my family. I couldn’t risk any of this because we live in a world where we know addiction consumes people and their families, but we still call it a choice. Silence became my friend because it was too difficult to explain how alone I felt; how much I wished I could be the child of an able-bodied mom and the successful father. The truth is though, this is normal for many in our country. Of the 2 million people in our prison systems, 500,000 are incarcerated for drug-related crimes. So if you’ve dealt with addiction or incarceration as a result of it, then you are not alone.

As someone caught in the aftermath of my parent’s addiction, choices, and incarceration, I saw the situation from a different perspective.

I wished I could break my silence and tell them about my reality and my pain. I wished I could tell them that my mom, siblings, and I were not involved in my dad’s decisions. My mom didn’t even know about the extent of his addiction. I wish I could go back and tell myself and everyone else what I know now; your parent’s actions and crimes do not define you. You do not have to follow in their path.

These childhood experiences colored the path for my development over the years. My dad’s addiction and incarceration was not a single moment that happened. His situation is something that I have grown and developed around. After my dad became incarcerated, I began to struggle with anxiety and trust issues. I felt unloved, and that I couldn’t count on my dad. After his release, this did not improve. My dad’s mental health began to deteriorate.

My dad had been diagnosed with bipolar type II disorder before, but the symptoms seemed to be mostly under control until his release from prison. It wasn’t uncommon for my dad to go through manic and depressive periods. For a period he would tell us “everything is going to get better” and then a month or few months later he would be self-pitying, disconnected, irritable, and we didn’t hear from him for months; once he didn’t contact us for two years. Although he was sober, the effects of his addiction and incarceration seemed to have lasting effects.

What was once silence, sadness, and confusion became intense anger.

Even though my mother was the biggest blessing in my life, I was angry at her even though she was just as much a victim as I was. Addiction does weird things to families. It causes you anger and grief, and somehow it becomes easier to lash out at those who are there than the one with the addiction. Addiction and incarceration strain families. Things do not magically get better after your parent is sober or is released from prison. This process takes time. There is a lot of “you owe us an explanation! Do you expect me to forget?” You were never there when I needed you growing up.”

I remember countless nights lying on the floor, sobbing over the way my life was. I was never going to be able to have honest relationships because I didn’t want to tell them about my dad. I didn’t deserve happiness. If I did decide to tell someone, they would just think that I’m too much to handle; that I have too much baggage. I didn’t think I was normal. I felt broken and worthless. For awhile, settling into this pain was a lot easier than forgiveness.

I have come to learn that I am my own person, capable of making my own decisions, independent of his decisions. There are a lot of things I learned by being the daughter of an addicted parent, and one is that yes, the experiences I have had have made me feel terrified, embarrassed and misunderstood, but they have also turned me into someone who is empowered, resilient, and insightful. To stay silent, would be to allow the negative things to control me.

I have a passion to do things differently. Doing things differently for me meant learning to understand my dad’s situation. It means not letting others tell me how I should feel about it, or how I should be healing. I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve been told that being angry isn’t the answer. But feeling angry is natural. Healing is a long, painful process. Eventually, I forgave him. I recognized that I cannot change what has been done, but things can change if I’m willing to try.

My healing process has given me a passion for social justice, and I’m no longer ashamed to talk about this part of my life.

Once I realized that I wasn’t alone in my struggle, it became easier to heal. It also gets easier as time passes. Today, my dad has been sober of his gambling addiction for a little over twenty-three years. At nearly sixty-seven years old, he regularly competes in Crossfit competitions and has recently become a certified personal trainer. Our relationship has come a long way from what it once was, but we are always working on rebuilding bridges. It is not a straight path. I am ready to take control of my path. My voice can no longer be silenced.